Build your own Probot

•

A lot of people look at Probot and wonder how they can extend it - add custom routes, integrate it with other platforms, control its startup. I firmly believe that too many features and options can make a framework unwieldy, so rather than show where all of those things can fit in Probot itself, we're going to take a look at building our own Probot.

Interestingly, the API design (started by @bkeepers) looks and feels a lot like a chatbot. I'm hoping that from this post, you (yes you!) will get an understanding of how Probot integrates with GitHub and why it feels easy to use, and then you'll be able to bring those patterns to your own projects.

I'm going to leave the Why we built Probot until the end because while it is interesting and enlightening, we want to build stuff!

A couple of important notes:

- Unless specifically stated, all code is pseudo-code, not copied directly from Probot. I'll be oversimplifying some code so that we don't have to think about edge-cases and complications.

- Many parts of Probot have been extracted into smaller modules (shoutout @gr2m). We'll talk about how they work, but you'll probably just want to use them directly.

- There's a lot of code here - if you're looking at something and wanting for some more explanation, please tell me!

Probot is an opinionated Express server

#At its core, Probot uses Express to run a Node.js HTTP server. When an event happens on GitHub that your Probot app is configured to care about, GitHub sends HTTP POST requests (webhooks) to a special "webhook endpoint," containing information in a JSON payload about what event was triggered. You can imagine code like this being a central part of the Probot framework (I'll link to actual code shortly):

const express = require('express')

const app = express()

app.post('/', (req, res) => {

// We got a webhook! Now run the Probot app's code.

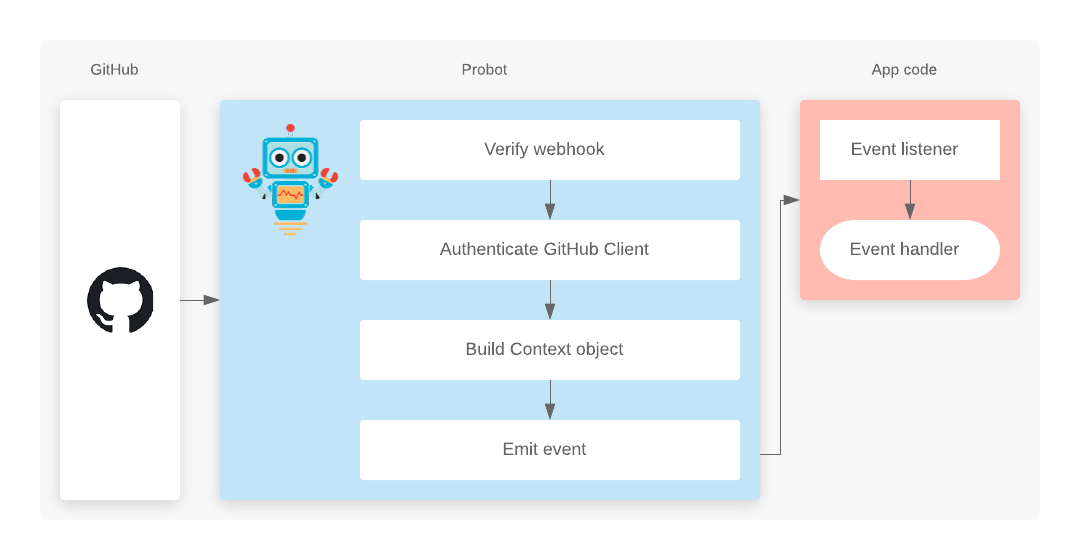

})When a Probot server receives a Webhook, it does a few things before actually running your code:

First, it verifies the webhook signature; along with the JSON payload, GitHub sends an X-GitHub-Secret header. The value of the header is a combination of a secret key and the contents of the payload itself. GitHub and your Probot app both have the secret key (Probot uses the WEBHOOK_SECRET environment variable), so when the two services generate the header they should match exactly. If they don't, Probot ignores the request.

This is a security measure to ensure that random POST requests aren't acted upon - only GitHub can trigger your app. This logic is now abstracted in a separate module that Probot uses, @octokit/webhooks, for convenience and reusability. Here's a contrived example of what Probot does internally:

app.post('/', (req, res) => {

// Grab the header that we should be able to create ourselves

const signatureHeader = req.get('X-Hub-Signature')

// Verify the webhook payload

const isValidWebhook = webhooks.verify(req.body, secretHeader)

// -> true/false

})Once the webhook verification is complete, Probot emits an event through its internal EventEmitter:

const express = require('express')

const EventEmitter = require('events')

const Webhooks = require('@octokit/webhooks')

const app = express()

const events = new EventEmitter()

const webhooks = new Webhooks({ secret: process.env.WEBHOOK_SECRET })

app.post('/', (req, res) => {

// Verify the webhook payload

const isValidWebhook = webhooks.verify(req.body, req.get('X-Hub-Signature'))

// The name of the GitHub event is sent in a header

const eventName = req.get('X-GitHub-Event')

// It's valid, we emit an event

if (isValidWebhook) {

events.emit('github-event', {

event: eventName,

payload: req.body

})

// We tell GitHub that everything worked great!

return res.send(200)

} else {

// Couldn't validate the webhook, so we send an "Unauthorized" code

return res.send(401)

}

})If you're paying attention, you'll recognize that @octokit/webhooks does a lot of potential event handling, very similar to EventEmitter (and Probot). This isn't a coincidence, @octokit/webooks was born from Probot's intentions - but I'm showing a little bit of what drives that logic instead of using it outright.

If your app is deployed to a public URL, GitHub can make an HTTP request; but if you're just working locally, you'll have to use something like localtunnel or ngrok to expose your local machine to the internet. We built Smee.io specifically for Probot, to receive webhook events locally - it's its own topic, so if you're interested in a post on Smee let me know!

Somewhere behind the scenes, Probot has registered the event handlers of your Probot app. A standard app looks like this:

module.exports = app => {

app.on('event', handler)

}Where app is an instance of the Application class, which is (sort of) an extension of `EventEmitter! We'll look at that shortly - there are still few a things that Probot does before running your code, but first...

Why an EventEmitter API?

#To me, it's the inherent simplicity of "something happened, so now run this code." When an issue is opened on GitHub, run this code. This lets you focus on your app code, and not care what Probot is doing under the hood. Similar to something like Express's app.get(), but this lets you register multiple event handlers for the same event, and have an infinite list of events (since they're just strings).

Authentication

#Next, Probot looks for a particular value in the JSON payload, installation.id. Along with your App's credentials (a Private Key and App ID), it uses that installation ID to create a temporary API token.

This was the most complicated part of Probot for a long time, until @gr2m pulled it out into its own repository, @octokit/auth-app.js. I'll talk about what it does, then show some code using it!

Two ways for GitHub Apps to authenticate

#If you're here, I'll guess that you're familiar with what GitHub Apps are. They're an "actor" on GitHub, and can authenticate in two distinct ways:

- As itself, as an app. Used for collecting stats about the app, or for access information about a particular installation.

- As an installation. When you install an app on an account (a user or an organization), that creates an installation. Each installation has a unique

id(the aforementioned payload value), and we can use that to create an API access token.

Usually, when your Probot app calls context.github..., github is an authenticated Octokit client that uses an installation token. We can get one of these installation tokens from GitHub, using a JSON Web Token (JWT) that securely proves our app’s identity to GitHub.

Authenticating as the app is done by combining the APP_ID and PRIVATE_KEY, using JWTs:

const jsonwebtoken = require('jsonwebtoken')

// A helper function for generated an access token using the App ID and Private Key

function getSignedJsonWebToken({ app_id, privateKey }) {

const now = Math.floor(Date.now() / 1000)

const payload = {

iat: now, // Issued at time

exp: now + 60 * 10 - 30, // JWT expiration time (10 minute maximum, 30 second safeguard)

iss: app_id

}

const token = jsonwebtoken.sign(payload, privateKey, { algorithm: 'RS256' })

return token

}We can then use that token to send a POST request to GitHub, creating an installation access token:

// Get an installation token

async function getInstallationAccessToken ({

app_id,

privateKey,

installation_id

}) {

// Create our token for making requests as the app

const signedJWT = getSignedJsonWebToken({ app_id, privateKey })

// Compose our API endpoint URL using the `installation_id`

const url = `https://api.github.com/app/installations/${installation_id}/access_tokens`

// Note: I'd recommend using `@octokit/request` here, but you don't

// need to. It's just an HTTP request!

const response = await request({

method: 'POST',

url,

installation_id,

headers: {

authorization: `bearer ${signedJWT}`

}

})

return response.data.token

}Code mostly copied from @octokit/auth-app.js which abstracts it all, through a handy method called getInstallationAccessToken! In practice, we want to say:

When we receive an event from GitHub, create an authenticated GitHub client and emit an event

The Application class

#Let's talk about this line here:

module.exports = app => {

app.on('event', handler)

}Probot apps export a function, where app is the only argument. Probot calls that function on startup with an instance of a class called Application. It has an API similar to the EventEmitter, with important methods on it for handling the lifecycle of an event, the most important of which is Application#auth.

Here's what it looks like (this isn't exactly Probot's code - I took some liberties to simplify the code and remove some edge-case handling):

import { createAppAuth } from '@octokit/auth-app'

import { Octokit } from '@octokit/rest'

class Application extends EventEmitter {

constructor () {

this.auth = createAppAuth({ ... })

}

async auth (installationId?: number): Promise<Octokit> {

// If installation ID passed, instantiate and authenticate Octokit, then cache the instance

// so that it can be used across received webhook events.

if (installationId) {

const installationAuthentication = await this.auth({ type: 'installation', installationId })

return new Octokit({ auth: `token ${installationAuthentication.token}` })

}

// Otherwise, authenticate as the app using a JWT

const appAuthentication = await this.auth({ type: 'app' })

return new Octokit({ auth: `Bearer ${appAuthentication.token}` })

}

}Along with some of the earlier code we looked at, we would use the Application class in code like this:

const events = new EventEmitter()

const application = new Application()

// This is code similar to what you'd find in your Probot app's code

application.on('issues', async context => {

return context.github.issues.createComment({ ... })

})

// We register an event in our internal EventEmitter, as a sort of middleware

// for our `Application` event emitter. When thats triggered, we create an

// authenticated GitHub client, and then emit an event using the webhook's event

// name, but on the Application instance.

events.on('github-event', ({ event, payload }) => {

const github = await application.auth(payload.installation.id)

const context = { github, payload }

return application.emit(event, context)

})

app.post('/', ...)A common question I hear is "how do I access context outside of an event handler?" - hopefully, this has helped explain how context is created and is dependent on the installation.id value of the payload. If you have another way to get an installation ID (possibly through API endpoints for finding an ID), then you can totally construct your own Context is similar object.

Loading your App's code

#This is a fun part of Probot - you write code that exports a function, but then Probot magically runs that function. Most Probot apps use a CLI the Probot provides, called probot run. For example, JasonEtco/todo's npm start command is this:

{

"scripts": {

"start": "probot run ./index.js"

}

}This tells Probot to require() the ./index.js file, and run the exported function with an instance of Application. That's done through Probot#load, and somewhere down the line we have code like this:

// From https://github.com/probot/probot/blob/HEAD/src/resolver.ts

import { sync } from 'resolve'

export function resolve (appFnId: string) {

// appFnId would be `./index.js`

return require(sync(appFnId, { basedir: process.cwd() }))

}We're loading the code via Node.js's require() functionality. Then, once we've got the function loaded up, we simply call it:

const application = new Application()

const yourApp = probot.load('./index.js')

yourApp(application)Calling the function then calls application.on(), which registers the event handlers!

While this isn't all of Probot, it really is the core of it. We get an event through the POST endpoint, use information from it to create an authenticated GitHub client, and run your app's code.

A very simple Probot framework

#Using all of the above information, I wanted to take a crack at a simplified version of Probot that, aside from the GitHub authentication mechanisms, has nothing to do with GitHub. You can take this framework and apply it to any other service that sends webhooks.

const express = require('express')

const EventEmitter = require('events')

const { Octokit } = require('@octokit/rest')

const { createAppAuth } = require('@octokit/auth-app')

const app = express()

// Get the `index.js` file of wherever you're running this server

const yourAppCode = require(path.join(process.cwd(), 'index.js'))

// Define our Application class, which handles the authentication logic

class Application extends EventEmitter {

constructor () {

this.auth = createAppAuth({

id: process.env.APP_ID,

privateKey: process.env.PRIVATE_KEY

})

}

async auth (installationId) {

// Get an installation access token for the given ID

const installationAuth = await this.auth({ type: 'installation', installationId })

// Return an Octokit client using the token

return new Octokit({ auth: `token ${installationAuth.token}` })

}

}

// Create and use our Application instance

const application = new Application()

yourAppCode(application)

// Create our internal EventEmitter

const events = new EventEmitter()

events.on('github-event', ({ event, payload }) => {

// Before running the code, we create an authenticated client

const github = await application.auth(payload.installation.id)

// Prepare our context object

const context = { github, payload }

// Emit the event

return application.emit(event, context)

})

app.post('/', (req, res) => {

// Verify the webhook payload. You'd probably want to use `@octokit/webhooks` instead!

const isValidWebhook = verifyWebhookPayload(req)

// The name of the GitHub event is sent in a header

const eventName = req.get('X-GitHub-Event')

// It's valid, we emit an event

if (isValidWebhook) {

events.emit('github-event', { event: eventName, payload: req.body })

return res.send(200)

} else {

return res.send(401)

}

})

app.listen(3000)This is a mostly functional Probot framework, but some immediate ways that Probot improves upon the above code:

- Probot loads multiple

Applicationinstances, with some "internal" apps. For example, there's a special Sentry integration that Probot loads as a Probot app itself! - Installation tokens are cached, to avoid making a ton of requests for the same thing.

Contextis a real class with helper methods.- Probot uses

promise-eventsfor clearer, Promise-based event handling. - Grabbing the

PRIVATE_KEYis a little more robust - Probot will look for a/*.pemfile, use thePRIVATE_KEY_PATHvariable, and thePRIVATE_KEYenvironment variable. - Loading your app's code is done in a smarter way -

index.jsis the default, but you can provide a specific path.

With that, I want to talk a bit about why I think Probot is, overall, a well-built project and what I've learned from it so far.

What makes Probot "good"

#By now, you've seen what makes Probot work - but its ease-of-use is explained better by some features we haven't talked about yet:

Documentation

#This should be obvious, but good documentation means people will be able to use the thing. If its really good, users of your library/framework/application will be able to hit the ground running with very little explanation, and if they want to they can learn about more advanced usage.

Probot's docs are solid - not perfect, but good. If you're looking to build something for other developers, don't ignore the docs.

create-probot-app

#This is a big one - Probot requires a few specific things to be setup correctly, including things like the npm start/probot run script and the environment variables. Without the create-probot-app scaffolding CLI, it'd be a lot more challenging for users with no context to set it up correctly. GitHub's Template Repositories are a new, lightweight solution that may work for you!

probot run

#We talked about how probot run works earlier, but an important thing to note is that without it, you'd be asking your users to write "boilerplate code." That's code that every single Probot app needs; if you can avoid it, maybe by shoving the logic into a CLI like probot run, it can simplify the end-users' experience.

One important note though: build your library in a way that doesn't require that CLI. For the longest time, starting Probot programmatically required reaching into its internals and calling undocumented APIs. Ideally, the CLI would simply wrap some functionality that's already exported, that users can choose over a CLI if they need more control.

Context helper methods

#We didn't talk much about the Context class, aside from creating context.github, but many Probot apps end up calling methods like context.repo(). This returns some data from the webhook payload, and takes an optional argument with additional data. You would use it like this:

app.on('example', async context => {

const params = context.repo({ title: 'New issue!' })

// -> { owner: 'JasonEtco', name: 'my-repo', title: 'New issue! }

return context.github.issues.create(params)

})In the above code, we're putting together an object to pass to an Octokit method. This is something you'll want to do often in a Probot app, so it was a case for a little abstraction helper. The code for it is really simple:

// https://github.com/probot/probot/blob/61c05ea76e9ea31fbdea15c99f7c1cc613321db5/src/context.ts#L106-L117

class Context {

public repo<T> (object?: T) {

const repo = this.payload.repository

if (!repo) {

throw new Error('context.repo() is not supported for this webhook event.')

}

return Object.assign({

owner: repo.owner.login || repo.owner.name!,

repo: repo.name

}, object)

}

}This was designed before the object spread operator was widely available, but you could choose to design this a little differently and use a custom getter (I took this approach with JasonEtco/actions-toolkit):

class Context {

public get repo {

const repo = this.payload.repository

if (!repo) {

throw new Error('context.repo is not supported for this webhook event.')

}

return {

owner: repo.owner.login || repo.owner.name,

repo: repo.name

}

}

}This is a really small getter, that just grabs some info from the payload. But you'll notice that we're returning an object with a much simpler shape ({ owner, repo }), and it maps perfectly to most Octokit methods' parameters. It's these small additions that make writing code with Probot just a little more smooth.

Why we built Probot

#I can't speak to the original motivation; Probot started before I came on board. But, here's my take on what it brought to the ecosystem, and how it helped push the topic of workflow automation forward.

Authentication is hard. GitHub Apps have a lot of authentication. If you want people to use your platform, it needs to be easy to use - and that's an immensely difficult balance to strike. GitHub Apps are an awesome platform, but there's a lot going on. This is where frameworks and tooling can come in to help us out.

JavaScript is an approachable language. You may not love it, it has its faults, but ultimately people use JavaScript. While GitHub is a Ruby shop, and a lot of examples and documentation for building GitHub Apps are in Ruby, the choice to use JS for Probot simply meant that more developers could use it without having to learn a new language.

It makes the hard stuff easy, and the advanced stuff is still hard. By that, I mean that you can write a fully-functional Probot app without having to poke at its internals or understand how it works under the hood. But, with a complex app (like GitHub Learning Lab, or the GitHub/Slack integration), you'll inevitably hit the limits of what Probot can do. That's fine - there are thousands of apps that are, for all intents and purposes, simple, but bring serious value (like Stale). That's because all the hard stuff is still there, just hidden away.

So I hope you learned something, or that this was interesting to you. I know I've been learning a lot working on Probot. If you have any questions, ask away!